The origins

Born as a Roman colony in 284 BC with the name “Sena Gallica”, the first Roman colony on the Adriatic coast, it soon became an important military and logistic base for the Romans.

After being sacked by the Visigoths, at the time of the Longobards’ invasion of Italy the city remained under the Byzantine rule, and together with Ancona, Fanum Fortunae (Fano), Pisaurum (Pesaro) and Ariminum (Rimini) it composed the so-called Byzantine Pentapolis. Senigallia was then involved in all the historical events up to the donation of the Pentapolis to the Pope’s State.

Over time the town experienced an interesting economic development and took part in the establishment of the so-called “Fiera della Maddalena” around the thirteenth century.

But during the Middle Ages it clashed with the interests of neighbouring cities, mainly with Fano, Jesi and Ancona, because of the conflicts between Guelph and Ghibelline factions in Italy. Senigallia was then conquered and largely destroyed by the troops of Manfred of Sicily, who had the walls demolished.

Renaissance

Senigallia (at the time known as Sinigaglia or Sinigallia) survived its decline until Pope Gregory XI charged Cardinal Egidio Albornoz of the restoration of the papal authority in the territory: the latter visited “the village” and planned a series of works to be carried out to bring it back to its ancient magnificence.

In the first half of the fifteenth century Senigallia, which was slowly recovering, attracted the attention and interest of Rimini’s ruling family, the Malatesta, thanks to its highly strategic position, just half-way between Ancona and Fano.

Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta became then the “re-founder” of the city.

Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta became then the “re-founder” of the city.

In addition to renovating the city it was necessary to repopulate and develop it, and to do so Sigismondo gave a new impetus to the old Fair of La Maddalena and established tax breaks for those wishing to move to the “new city”, attracting many people from various parts of Italy.

However, the reconstruction was so expensive that it forced the Malatesta family to get into debts with Pope Pius II, who took possession of the city and gave it first to Antonio Piccolomini and then to Giovanni della Rovere, who received the title of Duke.

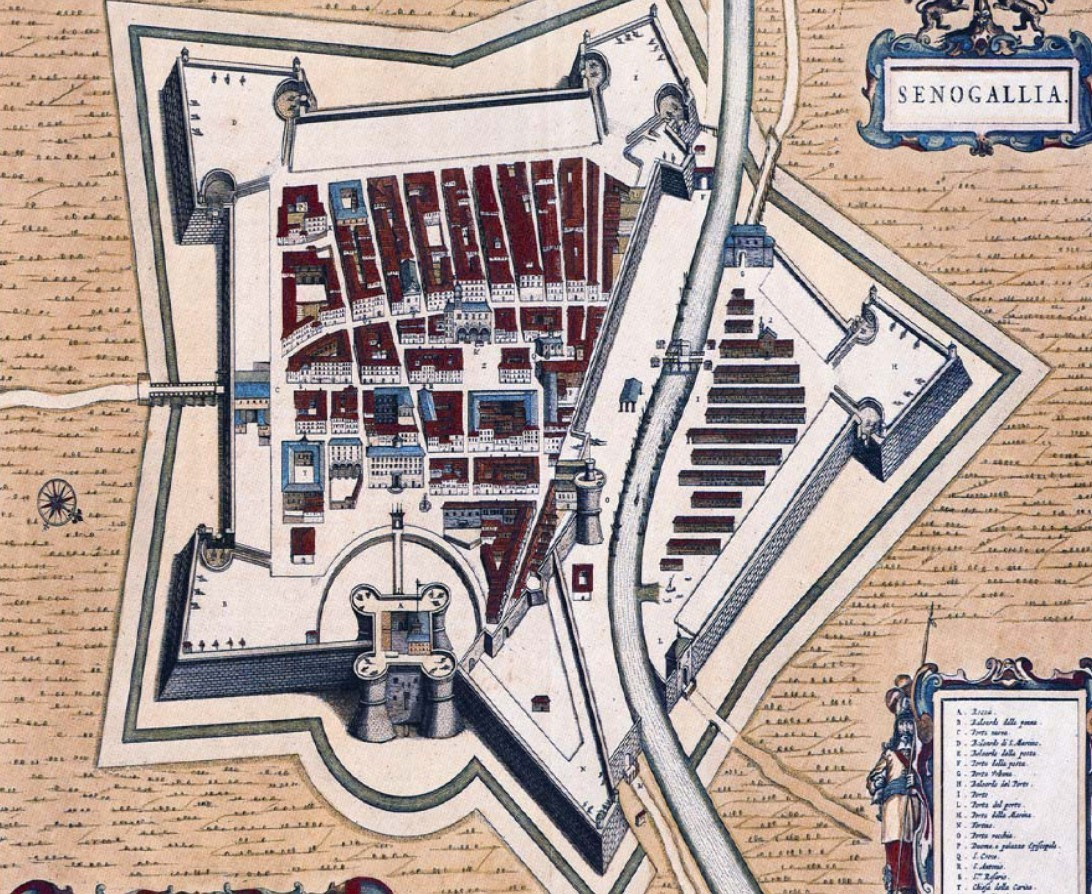

Giovanni died in 1501 after 27 years, leaving the city modernised, with new and larger walls around the fortress which was guarded and equipped to defend Senigallia on the side of the sea. He also completed the reclamation of the marsh.

At the turn of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Senigallia fell for a short period under the rule of Cesare Borgia, the famous Duke Valentino, described as an example of homo novus in Machiavelli’s “Il Principe” (The Prince). A few years later, supported by his father Pope Alexander VI, he managed to create a personal domain that extended from today’s Romagna until the north of the Marche, becoming in fact a powerful local ruler.

He became famous and is mentioned in historical chronicles (by Machiavelli), for the meeting that Duke Valentino offered to his old local allies, who had become traitors and enemies, but who eventually repented and were kindly invited to the city with the purpose of finding a peaceful and long-lasting agreement. The story ended, however, with a ruthless revenge known as the massacre of Senigallia, in which the Duke had his guests arrested and killed by his armed men.

Valentino’s experience ended in 1503, when a banal illness prevented him from taking part in the intrigues for the election of the new Pope, the successor of his late father. Peter’s throne was then assigned to Julius II della Rovere, who took away the domains obtained so far by returning them to his relatives.

Meanwhile, the Maddalena Fair, which later became the Fiera Franca (meaning that no customs duties were to be paid), had established itself as one of the most important fairs in the country, with trade in goods coming from every corner of the Mediterranean.

In the eighteenth century the Fair became so important for city business activities that an enlargement of the city became necessary. This was done breaking down the stretch of the walls that skirted the right bank of the river Misa where the first arcades were built, dedicated to Cardinal Luigi Ercolani who directed the works.

This first enlargement was not sufficient, and another one followed in the eighteenth century with the construction of the last part of the historic centre which acquired its present configuration, and of the building that now hosts the State Police Station. More arcades were also erected along the river, up to today’s Viale Leopardi. On one of the ramparts facing south, enlarged by an extension, the city theatre “La Fenice” was built, homonym of the more famous Venetian theatre.

ca. 1865, Vatican City — Pope Pius IX — Image by © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw the Napoleonic dominion in Italy and the subsequent restoration of the Pope’s power, but it also saw the birth of the heir of the noble local Mastai Ferretti family, the young Giovanni Maria who is known in history as Pope Pius IX, beatified on September 2, 2000 and last king of the Papal State. Ascended to the papal throne in 1846, his pontificate lasted a good 32 years and was the longest in history after the traditionally recognised Peter the Apostle.

With the unification of Italy, Senigallia was included into the newly formed Province of Ancona. But for Senigallia the national unity also involved the definitive loss of the Franca Fair (officially in 1869, but it already started its decline years before) and tourism became the main economic activity: Senigallia was among the first cities to promote itself nationally and international as a place of leisure and rest, taking advantage of the beach that in a few years was nicknamed the “velvet beach” and which is still a tourist landmark. From the shore, the view is stunning: unlike most of Adriatic tourist locations, which have a straight coastline, Senigallia enjoys a beautiful panorama of the Gulf of Ancona.

In 1853 the first beach resort was built, which in fact marked the beginning of Senigallia’s tourist vocation, which was later associated with the theatre season.

1900

At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries Senigallia already had an important tourist value which increased in the following years: symbols of this phenomenon were the Stabilimento Bagni beach resort (now an abandoned building) and the Rotonda a Mare, a former palafitte built in front of the Stabilimento Bagni and rebuilt in its current position in reinforced concrete in 1933 after the earthquake of 1930.

The confirmation of the important role that the city had acquired for tourism came in 1928, when Senigallia and Cortina d’Ampezzo in the Dolomites saw the establishment of the first Italian Tourism Agency offices.

In the meantime, the city continued to develop its urban areas with the first social housing and residences outside the walls.

Then Senigallia was hit by a massive earthquake on October 30, 1930, whose damages were particularly heavy for the city: the theatre suffered serious damage, the old bishop’s seminary had to be demolished and moved out of town, a convent of nuns (where the famous historical massacre of the Duke Valentino took place) was completely demolished to make room for the current G. Pascoli elementary school, Porta Saffi (located at the beginning of Corso II Giugno) was demolished opening the view over the main mall from to the rest of the city out of the walls. In general, the whole city suffered damages that made it necessary to reduce the height of almost all the buildings of the current historical centre and imposed a drastic change in its structure.

The seismic event had as a further consequence the opening of the city to the outside, with the urbanisation of the area south of the historic walls and the construction of social housings.

Luckily enough, the passage of the troops of WW1 And WW2 left in the city only few signs that are still visible today: bullet holes can be seen at the Foro Annonario square and the main bridges needed to be completely rebuilt.

Subsequently, the city went through a period of strong growth and a sign of its recovery was the return of tourists. Over the fifties and sixties Senigallia rivalled with Rimini as the main national seaside resort, the latter being historically associated with the motoring season and shows.